Recently, Sonder’s Dr Jamie Phillips was invited to debunk five myths of employee wellbeing for members of the Corporate Mental Health Alliance Australia. Having personally made mistakes in the past, this is a topic Jamie is passionate about, as he endeavours to help others follow evidence-based practices rather than hearsay, to ensure they are providing the most meaningful support possible to their people – and they are not unknowingly increasing their organisational risk.

We invite you to watch the video below and/or read the associated transcript.

Presentation

Presenter

Dr Jamie Phillips MB ChB, AFCHSM, DIMC RCS(Edin), MRCGP(UK), FACRRM(EM)

Dr Jamie Phillips is a commando-trained military officer, who served for 20 years in the UK Armed Forces and Australian Defence Force as an embedded doctor and operational commander on multiple combat operations around the globe. He is a specialist rural and remote physician, with advanced specialist training in emergency medicine.

As Medical Director at Sonder, Jamie helps Sonder provide safety, medical, and mental health support to our members worldwide. He is also a practising physician working in emergency medicine.

Transcript

Hello, my name is Dr Jamie Phillips, I’m Medical Director at Sonder, and I’m also a practising physician, working for the last 20 years in remote and rural medicine and emergency medicine. And it’s for that reason, I’m afraid, that I’m not able to join you in person today. Unfortunately, at short notice, I’ve been asked to provide emergency medicine care here in my community in South East Queensland. So, unfortunately, I won’t be able to join you in person, but I’m sure the team will look after you well.

It is, however, with a real pleasure that I get to present on something that’s very close to my heart. This document, 5 Myths of Employee Wellbeing: An evidence-based approach for decision-makers. This is a document that we produced last year, really as a result of our journey in developing our own model of care within Sonder. As an accredited healthcare provider, it is essential that we only provide evidence-based interventions for all of the people and the families and the communities under our care.

And as we went on that journey of developing quite a unique model of care to support our members and their employers, we realised that a lot of this information isn’t freely available. And whilst it’s present, it’s very, very hard to find. And so we thought it would be a good idea to produce a document that tackled some of the myths, some of the misinformation surrounding the five key areas of wellbeing that we were seeing with our many, many patients every single day.

I don’t think any of us appreciated how impactful it would be, but also how much discussion and sometimes hostility it would produce. So, I think there was a period where I was probably one of the most unpopular physicians and certainly one of the most unpopular clinicians working in this area in Australia. But I guess we had to be willing to be wrong, and we had to also be willing to be unpopular if we’re actually going to create something quite remarkable.

I think, however, as people have started to read the document – and I encourage all of you to read the document – people realise that the evidence is actually there, and the evidence is good, and it’s high quality. And it actually challenges a lot of dogma that’s been around this place for quite some time.

Health care in 2023

Certainly, as a doctor working in health care in 2023, after the last few years, more now than ever, people demand high-quality, effective, safe, evidence-based care, in the way that they want, how they want, where they want, and care that puts them in the driving seat and gives them that control. And you’re expected to deliver all of that against a really, really good value-for-money proposition as well. And I think that’s reasonable. And hence why we’ve coined this phrase, Active Care. A bit like streaming your TV shows or going shopping, really, health care should be the same; you should be able to demand health care that’s safe, and effective, and evidence-based – but delivered in the way that you want, and when you want, using platforms that you want to use, so you feel like you can take active control within a very overwhelming and confusing healthcare service.

Because often that’s what I see. I see huge health inequalities in emergency medicine, where people who are struggling to access care really don’t know where to turn, so they end up in the emergency department, and they end up seeking care, really, that they don’t ever need or probably should never have needed to get to that stage.

So this is something that’s very close to my heart, and I make no apologies if I speak about it very passionately. I also make no apologies that actually some of what I’m going to say may make you feel quite uncomfortable.

Being comfortable with being uncomfortable

Indeed, I, as a leader and as a clinician, have felt quite uncomfortable when we start to research on these topics, because I realise that in the past, I’d been guilty, both as a clinician, but also as a leader, about promoting and endorsing practices that have now turned out to be probably not as effective as we thought they were and then sometimes unsafe.

And when you go through that journey and you realise something maybe wasn’t as effective as you thought it once had been, and particularly if you’ve put your professional relationship on the line with other people to endorse it, that can be quite confronting, and it can make you feel quite uncomfortable.

But what I have learnt over 20 years in medicine is that sometimes that feeling of discomfort is the key for growth. And as we go on a journey from becoming unconsciously incompetent (i.e. we don’t know what we don’t know), to being consciously incompetent, realising what we don’t know, you feel uncomfortable. But it’s that feeling of discomfort that signifies that that’s the moment where real growth can occur and something quite remarkable can happen.

Employee wellbeing statistics

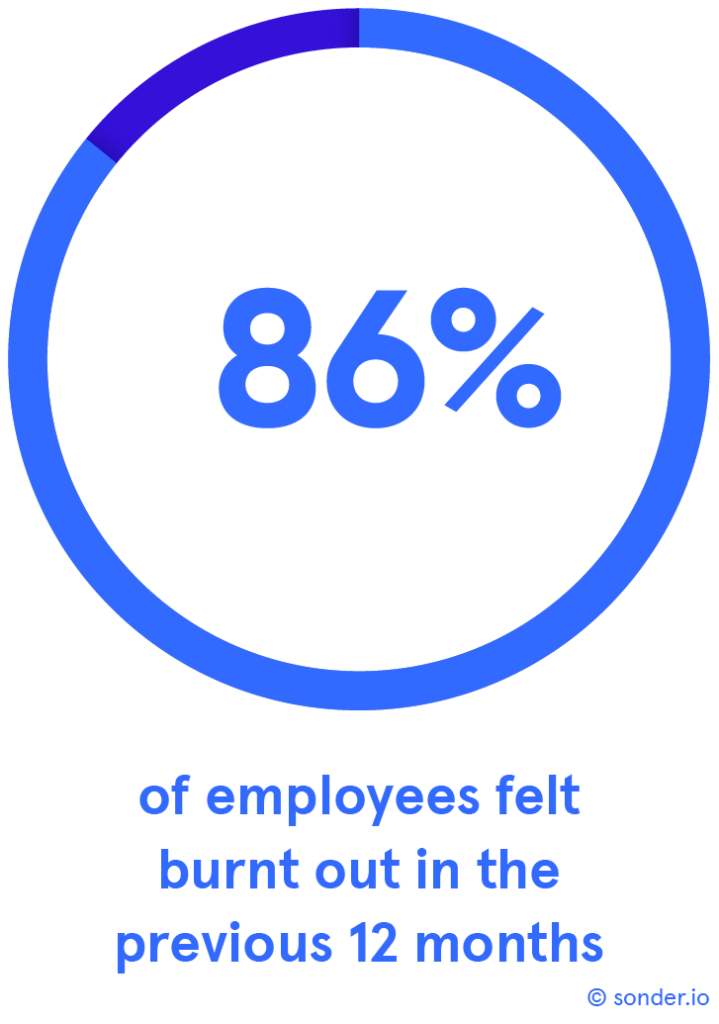

Because actually, employee wellbeing really, really matters. I say that as a doctor, but I also say that as an employer as well. A study we conducted last year showed that it’s a real problem for people. [Reference: Sonder survey of 2,000 employees working a minimum of 20 hours per week.]

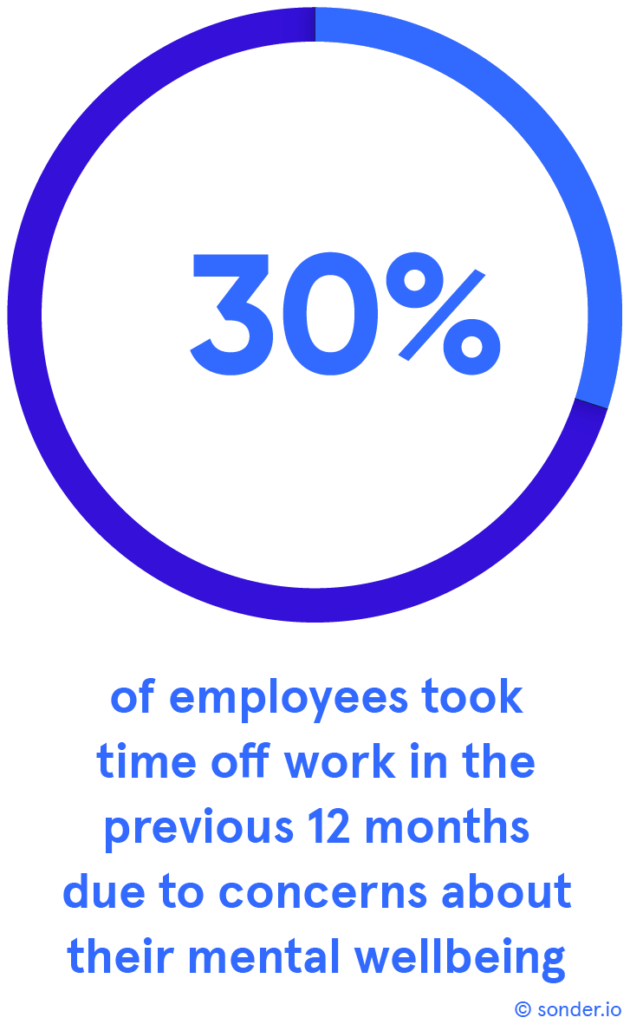

86 per cent of employees report feeling burnt out within the last 12 months, and of those employees, 30 per cent have taken time off from work in the last 12 months due to concerns about their own mental wellbeing.

So, that’s one-third of the workforce within the last 12 months have had to take time away from work with concerns about their own mental wellbeing. And that’s not without its costs.

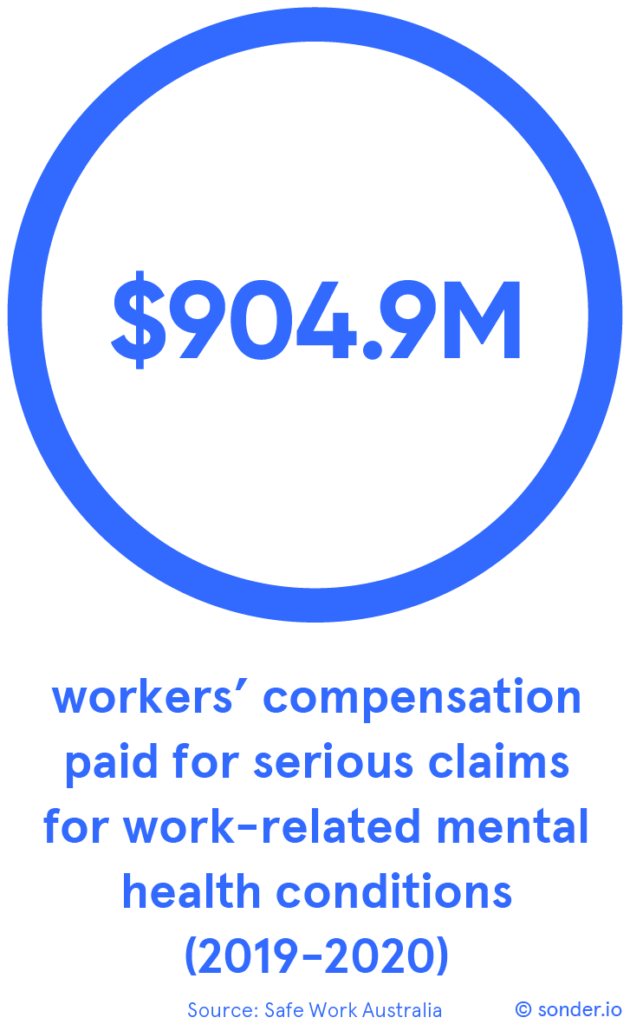

I mean, the claims – if you look at the claims data from Safe Work Australia, suggest that in the 2019-2020 period, they paid out over $900 million for serious claims for work-related mental health conditions.

And that’s not just primary mental health conditions (i.e. a condition that has been caused by the workplace), but also secondary mental health conditions, where other wellbeing issues, whether they be physical or occupational, have been sub-optimally managed, and maybe not been nipped in the bud, and as a result have gone on to lead to a significant mental health diagnosis.

So, whilst not managing wellbeing effectively is important for individuals, it’s also important for employers, and it’s also important for the wider business community.

5 myths of employee wellbeing

So, of the five myths, they’re all quite interesting, they’re all very different. I’m actually going to focus on two, which I’ll really dig into in depth then, but I’d like to give you an overview of the five and maybe promote a bit of interest in you to engage and read the other data behind them.

Myth 1: Paid time off cures burnout

So, myth one is that paid time off cures burnout. And this is a very popular theory that, you know, lots of businesses talk about being able to give time off to help people, so they don’t burn out. The evidence just doesn’t back that up.

What the evidence seems to show is that, yes, giving extra paid time off does seem to act as a bit of a band-aid for the situation, but it doesn’t address the underlying cause.

And the best analogy I can think of is if you’ve just done some gardening at your house and planted your favourite plants there and put some lovely fertiliser down, but inevitably the weeds start sprouting up.

And yet you can pull the weeds out or chop them back, but if you don’t remove the fertiliser, they’re just going to grow back. They’re just going to. Those sprouts and those shoots are just going to come back.

And what you actually need to do is say, okay, I’ve put in all this work, but actually, I need to remove that fertiliser, identify where the real underlying roots are, remove those roots, and then put the fertiliser back so the plants can grow.

Myth 2: Digital-only is the answer

Myth two, and this is a difficult one for me as a doctor who works for a technology company, is that digital-only self-help tools are the answer. Because it would be great if that was true. It would enable me to scale the health part of Sonder really, really easily.

But it’s just not true. What the evidence shows is that self-help apps are useful in terms of an introduction on initial guidance, but they should complement, not replace, professional, well-governed, health and wellbeing support.

It is important that we have the right balance of technology and the right balance of humans to make sure that we look after our people in a safe, effective, and reproducible way.

And I’m going to talk about that some more in a few moments.

Myth 3: Wellbeing cannot be measured

Myth three is that wellbeing cannot be measured. And for many years, people have said, well, we don’t measure it because we can’t measure it. And the evidence says that’s probably not true.

Certainly, the World Health Organization has very clearly defined wellbeing now. They’ve expanded on the definitions and have really encouraged people to think about wellbeing as not just the absence of ill health, but also a dynamic state of… how an individual, a family and a community exist, live, interact, and want to grow.

Where we do have a problem is there seems to be no internationally, or certainly nationally, agreed measurement standard. And that’s something that we’re very keen to work with our colleagues with, to start to define. Because if we’ve actually… got a measurement standard that we all agree on, we can start to compare results, not just hold onto our own results as well.

Myth 4: Employees need psychological debriefing after traumatic events

Myth four, and this one can be quite confronting for leaders, particularly leaders who have spent large amounts of money currently or in the past on employing programs, or contracting programs, that involve psychological debriefing.

So, myth four is that employees need psychological debriefing after traumatic events. And this is something I, as a leader and as a clinician, used to believe deeply and advocate very strongly for. But the evidence says different… [as it] may do more harm than good and may actually increase the risk of going on to develop psychological problems.

Again, we’ll dig into that a bit further in a few moments.

Myth 5: Perks keep people engaged

Myth five is that perks keep people engaged. Ping pong tables, yoga, food – they’re all really, really nice, they produce bursts of happiness, but they don’t seem to keep people engaged.

And certainly, what the evidence shows is that evidence-based health and wellbeing interventions that are delivered in a structured and data-driven way are much more effective at producing prolonged, sustained, and reproducible improvements in health and wellbeing. They’re not just these sugar hits that make people feel well in the moment but don’t really help in the long term.

Deep dive into myth 2 (Digital-only is the answer)

So, yeah, as I said, we’re going to focus on two of the five myths, but I strongly encourage you to read all the other three. And again, I make no apologies that some of this may make some of you feel a little bit uncomfortable. Certainly, even when we were writing this, a lot of our team started to feel uncomfortable as leaders, and I, indeed, felt uncomfortable as a clinician, because I reflected on the fact that I’d advocated for things that actually evidence didn’t back up in the past.

So myth two: digital-only tools are the answer in the wellbeing industry. And although that would be great if that was true, it would enable me to scale the health part of the business really, really effectively, and also help me to expand the business rapidly. But it’s just not true.

We know that people like digital health, particularly in Australia. I mean, certainly, COVID has been excellent for Australia to bring it forward over the last three to four years and accelerate our growth in terms of tech health.

If you look at the data here coming out from the University of Queensland Centre for Online Health, what it shows is that there was a massive expansion in telehealth consultations during the COVID period.

If you look around at the bottom table there, approximately one-quarter of all Medicare rebate-able telehealth consults during COVID…sorry, one-quarter of all consults that took place during the COVID period were done virtually by telehealth.

And there were a lot of people who said, oh well, that’s just situational. Once COVID goes, everybody is going to go back to face-to-face. That’s not what the evidence shows. What the evidence shows is that, yeah, about a quarter of consults, still, post-COVID, are happening via telehealth.

And then on the other side, there were people who said, well, this is now about the revolution, we can get rid of face-to-face, we can get rid of bricks and mortar, we can get rid of it expensive clinicians like myself, and we can just use AI and self-help apps to deliver wellbeing support and health support.

Unfortunately, that’s not true.

And this beautiful study from Edith Cowan University [ECU] published last year produced some really, really insightful data for the first time ever in Australia. And what they did was they had a look at the quality and the safety of the diagnostic and triage advice apps provided free online used by people in Australia.

I mean, what they did produce… they coined the phrase, cyberchondria, which is something I’ve started to use now. And they were really discussing [was] that 40 per cent of Australians now regularly use Google, consult with Dr Google, before they consult with a health practitioner to see if they get those symptoms.

And they do that in good faith, believing that like many aspects of their life, Google is going to help them do that. And indeed, they dig into it further in this study and show that 38 per cent of people presenting to Australian emergency departments have Googled their symptoms before they come.

And this is something that I see regularly in my practice. You know, Dr Google is a common colleague of mine, but not always the most faithful. And that’s what this study from ECU shows us, that accuracy of online triage tools and diagnostic tools is not that great. Only one one-third of the time, 36 per cent of the time, do they produce the correct diagnosis.

And actually when you dig further what you’ll find is only 58 per cent of the time does the correct diagnosis occur in the first ten hits (i.e. in the first page of Google does it get anywhere close to the correct diagnosis), meaning that 42 per cent of the time, the correct diagnosis is hidden. And as we all know, very few people click on to the second page of Google.

And then, for me, in emergency medicine, what’s really concerning is that only 30 per cent of the time do the online triage apps get the priority (i.e., emergency or routine) correct.

What does that mean? Well it means people are getting sent to the wrong places, with the wrong urgency, with the idea of an incorrect diagnosis… in care at all, and therefore experiencing worse or catastrophic ill health and mental health problems.

What this study also showed was that these online symptom checkers and diagnostic tools are highly risk-averse.

That results in us overservicing the population. And I think everybody has had that experience whenever you call Healthdirect – we always joke in emergency medicine that the end state of Healthdirect is always, “go to emergency”.

And that’s what this study seems to show, that it’s highly risk-averse, the process. As a result, people end up being overserviced.

What does that mean? Well, there’s massive amounts of unnecessary cost for the individual, but also for the federal taxpayer as well. And there’s large amounts of wastage in health service. Lots of people presenting unnecessarily for urgent or emergency care means that there’s huge amounts of wastage in that system.

What does that mean? Well it increases costs, which inevitably reflects in increased premiums for insurance, and increased cost in terms of taxation.

But it also produces an access block. And that’s something we hear a lot about in the media at the moment – six, seven, eight-hour waits in emergency [departments].

EDs are closing around the country because they can’t take any more people because there are so many people waiting to be seen.

We also hear about two, three, four-week waits for general practice.

All of this contributes to access block, reducing health equality, and widening the gap between the haves and the have-nots.

What does that mean for employers? Well, it means that people are spending longer away from home, and longer away from their families, and longer away from work, seeking medical care.

So, there’s a net cost to everybody, not just the taxpayer – it’s to employers as well.

Because the bottom line is, it’s about people caring for people. And that human interaction, we know, is essential to the care journey for all patients. There’s very good evidence showing that it improves health outcomes, and certainly at Sonder, we demonstrate that quite clearly we improve health outcomes, but we also get a much higher NPS…

We see that people, when they interact with clinicians, after using a tech platform to gain access to that clinician, the NPS… is much higher, and they are much more likely to come back and use us again, and also use us for their family and their loved ones.

So, in summary, myth two, “Is tech alone the answer?”, no, it’s not. A hybrid of… between tech and humans, the right amount of tech, the right amount of human, is probably the right place to be, based on the evidence at the moment.

Deep dive into myth 4 (Employees need psychological debriefing after traumatic events)

So, myth four. This is one I’m very, very passionate about. I’m very passionate about it because I made mistakes. I previously served in the military for 20 years, and when I first started my journey as a young military medical officer deployed in Afghanistan, I advocated very, very strongly for psychological debriefing for the men and women under my care and under my command.

I did that because I was told it was the right thing to do. Senior officers told me it was absolutely the right thing to do, and they told me that this was the best thing I could do to help my people.

And what I was doing, I was practising eminence-based medicine rather than evidence-based medicine. I was listening to my senior officers and I didn’t question the evidence. I blindly followed that evidence, and my senior officers and I strongly advocated for psychological debriefing.

Unfortunately, around that time, 2002-2003 in the UK, there came a seminal paper published in the British Medical Journal, and it called into question psychological debriefing.

It said that actually psychological debriefing may not be in the best interests of our patients, and it could cause harm. And I reacted how many leaders reacted about this in the past. To be honest, I buried my head in the sand. I’d staked so much of my own personal professional relationship and emotional collateral… I guess, in this process of psychological debriefing, that I said, no, no, it can’t be true, it’s only one study, I’m sure there’s much more evidence that supports it, and I stuck to that approach.

Unfortunately for me, as a leader, unfortunately for my patients, more evidence started to come out. 2005, 2006, 2007 – the evidence… The National Institute in Clinical Excellence in the UK said, no, there is no evidence to support psychological debriefing, and there is very clear evidence that it can increase the risk of mental health conditions, particularly anxiety, depression, stress, and also PTSD.

And that was a seminal moment for me. I felt deeply uncomfortable, and I felt deeply embarrassed that I’d been strongly advocating for a treatment that now seemed to cause harm. That actually we’d been paying for a treatment, as leaders, to reduce our risk profile, when, in fact, that treatment was increasing our risk profile.

And there had to be a huge amount of change management we had to do within the organisation to say, hey, I hold my hands up, do you know what, we got this wrong, in the face of the new evidence, this is what it shows. And we met with some resistance.

There were people who, like me back in 2003, 2004, didn’t want to hear the evidence. And I had to find a way to gently encourage them to look at the evidence, to get comfortable with feeling uncomfortable, to understand that what they were going on was a journey, moving from being unconsciously incompetent to consciously incompetent, and actually embracing that process.

Now that was very UK-focussed, and actually, luckily, by 2012, it was starting to spread internationally. Indeed, the World Health Organization, in 2012, came out and made the very clear statement that, with immediate effect, psychological debriefing is to cease – it is of no benefit and seems to increase the risk of harm.

Around that time as well in Australia, Australia produced its first national guidelines for the management of potentially traumatic events, and those guidelines were updated in 2021 and again in 2022.

And here you can see an excerpt of these very big, very complex guidelines.

What we should do is engage in psychological first aid, with a focus on monitoring their wellbeing, stabilise it if we need to as clinicians, but generally using the existing support network they have. We promote their self-care advice, we encourage them to engage socially with the networks that they have, we encourage them to reduce or limit their alcohol or drug use, and then we say we’re going to follow you up. And this is very, very clear, because actually what we’re talking about is psychological first aid.

Psychological first aid

Now, psychological first aid, what is it? It’s a simple, non-clinical, non-clinician led, peer-driven, peer-led system to encourage people to do what they naturally do. It creates a framework and a governed framework around what people will naturally do if we let them manage potentially traumatic events. And it has five key components.

Number one is we just make sure everybody is safe and everyone feels safe. Second thing is, we promote calm. Say to people, we acknowledge the experience that you had, but it’s going to be fine, you’re safe now, you’re in an organisation that cares about you, and we’re going to let you manage this in the way you want to manage it.

Because you must encourage self-efficacy. We don’t give our people enough credit. There is this culture where we feel like we should promote psychological debriefing for everybody, because we are well-meaning, we want to do something.

But actually, the statistics don’t back that up. The vast majority of people, 90 plus per cent are going to have no adverse reaction whatsoever to a traumatic event. They feel a bit unwell, they may feel a bit unhappy, but ultimately very, very quickly, they will recover back to their baseline and carry on with their life.

A small percentage may have a little bit of what I call a “speed wobble”, but they will use their normal existing network, they’ll use their normal friends and family, communities, leaders within their community, maybe even their GP, who will follow the national guidelines, but they’ll be absolutely fine.

And you do that by encouraging people to connect. And that’s something that’s very easy as leaders to do. As leaders, you can encourage your people to have situations, not forced, but they have opportunities to interact. They feel safe to talk, but they don’t have to talk.

And there’s no structured debriefing, it’s just saying, it’s fine, you can talk amongst yourselves, please let me know how I can support you to do that.

And you instill hope, you let people know that, yes, the evidence shows you’re going to be absolutely fine, but if you do need support, it’s there.

Because this is what the evidence shows actually about potentially traumatic events. If an individual has gone through that event… point, they feel that they may need some additional support, that’s when they need to be connected to professional medical care. Not in the immediate aftermath – that seems to increase risk. We’re then saying… in a delayed way, after having applied psychological first aid to the process.

And what you’ll see here on these Australian national guidelines is actually the only treatment that they explicitly recommend against is psychological debriefing. It is the only treatment that they say, you must not do it.

And it’s psychological debriefing as individuals, but also psychological debriefing as a group. Why? Because they’re following the evidence. And the evidence shows us that well-meaning as it may be, utilisation of psychological debriefing after potentially traumatic events, is at best neutral (i.e. it has no effect, no benefit), but it probably causes harm. And it may increase the risk of psychological problems down the line.

So I’ve told you what you shouldn’t use. What should you use?

Well, after using psychological first aid in the initial response, it’s about opening up systems to allow people to be connected… to support in the way they want, how they want, in an active way.

And the evidence-based approach, as you can see down there in the dark green, it’s a stepped care model. And what is that about? It’s about connecting people with the level of care appropriate for them in the moment.

Making that easy for them to access and allowing them to do it at their own pace in their own way. If they feel, working with a clinician, they need to escalate up the care, moving through to more advanced care, it’s available to them 24/7.

Conversely, if they feel that they need to move down the stepped care model, they can do that as well. It’s about giving the patient control.

Other two modalities – trauma-focussed CBT and EMDR. And again, evidence-based… cause no harm, seem to be of benefit.

Summary

So, in summary, noting how short our time is, there’s five myths. All five, I hope, will maybe encourage people to learn something. But more important, maybe encourage people to feel a little bit uncomfortable.

I personally am very, very passionate about getting the word out about myth two and myth four. Why? Because I made mistakes in that area myself as a leader and as a clinician.

But actually, acknowledging that as a leader, and then following the evidence and implementing evidence-based interventions, has made a huge impact for my people under my care.

But also has been great for me as a leader, because actually I can confidently say now that I’m using evidence-based interventions to support people.

And I guess maybe the final thought is that maybe the reason I chose myths two and four is because nobody else is willing to say it.

And I’m fortunate to work for an organisation that lets me sometimes risk being unpopular, and we risk being unpopular because we have to do what’s right.

Download the report

This evidence-based report will:

- Help you design employee wellbeing strategies that are evidence-based

- Share references and statistics you can use for your business case

- Dispel employee wellbeing myths that may be costing you time, money, and ESG results

Want to learn more?

For more information about how Sonder can help you rethink your employee and/or student support, we invite you to contact us here.

About Sonder

Sonder is a technology company that helps organisations improve the wellbeing of their people so they perform at their best. Our mobile app provides immediate, 24/7 support from a team of safety, medical, and mental health professionals – plus onsite help for time-sensitive scenarios. Accredited by the Australian Council on Healthcare Standards (ACHS), our platform gives leaders the insights they need to act on tomorrow’s wellbeing challenges today.