Last month, following the tragic bus accident in the New South Wales Hunter Valley that killed 10 innocent wedding guests, a spotlight was once again shone on the practice of psychological debriefing. Richard Bryant, Professor and Director of the Traumatic Stress Clinic at UNSW, contributed his perspective in The Conversation, and asked, “If there is so much evidence, why do we keep having this debate about the optimal way to assist psychological adaptation after disasters? …We need to develop better strategies to ensure we are meeting the needs of the survivors, rather than the counsellors.”

In the workplace context, psychological debriefing immediately after a traumatic event has long been offered by employee assistance programs (EAPs). However, practice is now outdated, and despite all the evidence showing that psychological debriefing can (a) do more harm than good and (b) potentially put employees and employers at risk, there are still companies out there providing this service – and well-intentioned employers continuing to pay for it.

What’s wrong with psychological debriefing?

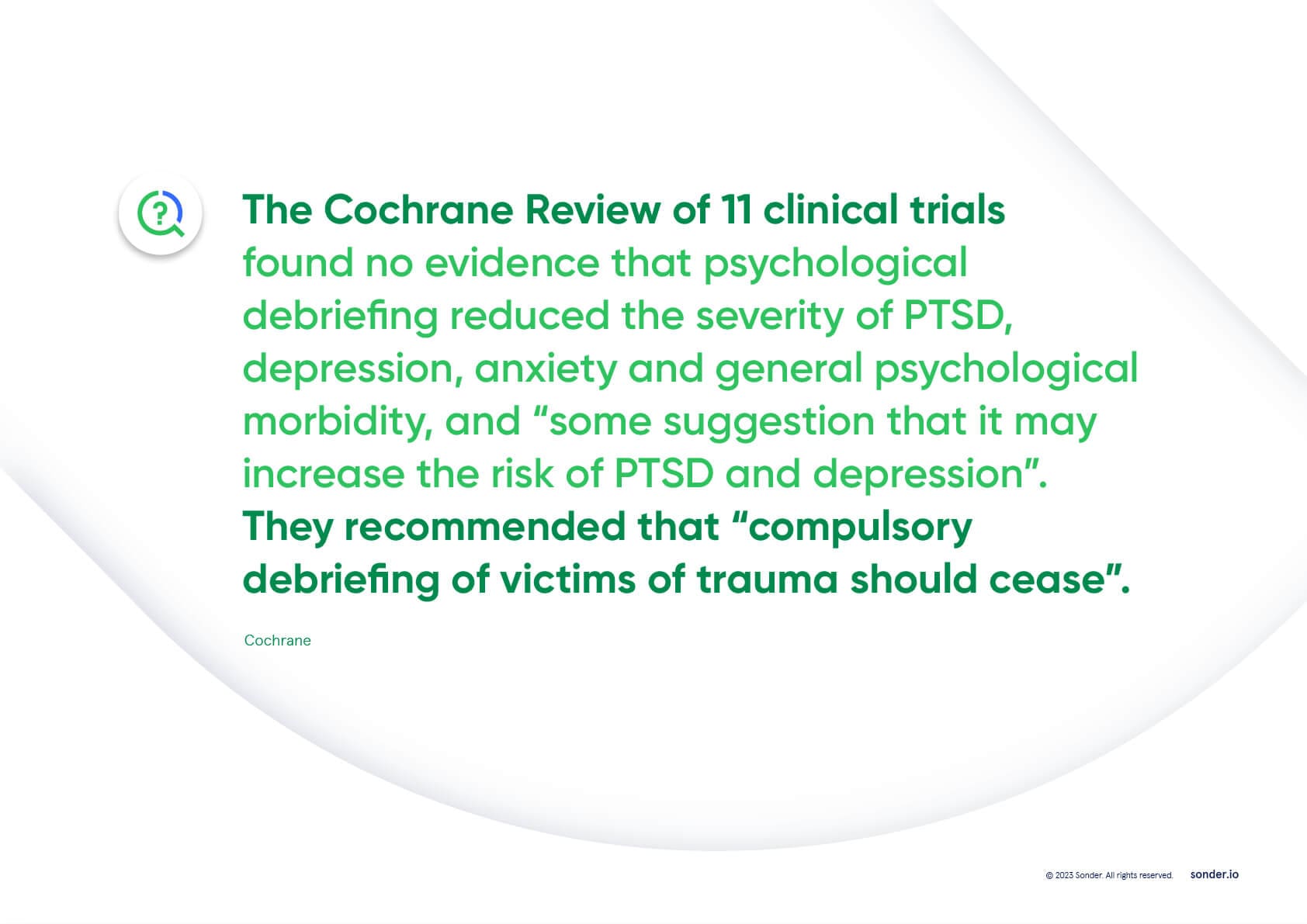

Psychological debriefing (including critical incident stress debriefing to reconstruct the traumatic event) is not the best clinical practice. The evidence has for some time suggested that, “psychological debriefing is ineffective and has adverse long-term effects. It is not an appropriate treatment for trauma victims.”

This sentiment was echoed in the World Health Organisation (WHO) literature review (2012) which concluded that “psychological debriefing should not be used for people exposed recently to a traumatic event as an intervention to reduce the risk of post-traumatic stress, anxiety or depressive symptoms”.

The belief that feelings must be shared

Professor Bryant noted, “The encouragement of people to discuss their emotional reactions to a trauma is the result of a long-held notion in psychology (dating back to the classic writings of Sigmund Freud) that disclosure of one’s emotions is invariably beneficial for one’s mental health.

Emanating from this perspective, the impetus for psychological debriefing has traditionally been rooted in the notion [that] trauma survivors are vulnerable to psychological disorders, such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), if they do not “talk through their trauma” by receiving this very early intervention.

[Consequently,] the scenario of trauma counsellors appearing in the acute aftermath of traumatic events has been commonplace for decades in Australia and elsewhere.”

“…It’s human nature to want to help,” offered Professor Bryant. But, “the evidence suggests we should monitor the most vulnerable people and target resources towards them when they need it – usually some weeks or months later when the dust of the trauma has settled. Counsellors might want to promote their activities in the acute phase after disasters, but it may not be in the best interest of the trauma survivors.”

Response from Dr Jamie Phillips

MB ChB, AFCHSM, DIMC, RCS(Edin), MRCGP(UK), FACRRM(EM), Medical Director, Sonder

“I’m very, very passionate about [not practising psychological debriefing] because I made mistakes. I previously served in the military for 20 years, and when I first started my journey as a young military medical officer deployed in Afghanistan, I advocated very, very strongly for psychological debriefing for the men and women under my care and under my command.

I did that because I was told it was the right thing to do. Senior officers told me it was absolutely the right thing to do, and they told me that this was the best thing I could do to help my people.

And what I was doing, I was practising eminence-based medicine rather than evidence-based medicine. I was listening to my senior officers and I didn’t question the evidence. I blindly followed that evidence, and my senior officers and I strongly advocated for psychological debriefing.

Unfortunately, around that time, 2002-2003 in the UK, there came a seminal paper published in the British Medical Journal, and it called into question psychological debriefing.

It said that, actually, psychological debriefing may not be in the best interests of our patients, and it could cause harm. And I reacted how many leaders reacted about this in the past. To be honest, I buried my head in the sand. I’d staked so much of my own personal professional relationship and emotional collateral… I guess, in this process of psychological debriefing, that I said, no, no, it can’t be true, it’s only one study, I’m sure there’s much more evidence that supports it, and I stuck to that approach.

Unfortunately for me, as a leader, unfortunately, for my patients, more evidence started to come out. 2005, 2006, 2007 – the evidence… The National Institute in Clinical Excellence in the UK said, no, there is no evidence to support psychological debriefing, and there is very clear evidence that it can increase the risk of mental health conditions, particularly anxiety, depression, stress, and also PTSD.

And that was a seminal moment for me. I felt deeply uncomfortable, and I felt deeply embarrassed that I’d been strongly advocating for a treatment that now seemed to cause harm. That actually we’d been paying for a treatment, as leaders, to reduce our risk profile, when, in fact, that treatment was increasing our risk profile.

And there had to be a huge amount of change management we had to do within the organisation to say, hey, I hold my hands up, do you know what, we got this wrong, in the face of the new evidence, this is what it shows. And we met with some resistance.

There were people who, like me back in 2003, 2004, didn’t want to hear the evidence. And I had to find a way to gently encourage them to look at the evidence, to get comfortable with feeling uncomfortable, to understand that what they were going on was a journey, moving from being unconsciously incompetent to consciously incompetent, and actually embracing that process.”

“…What we should do is engage in psychological first aid, with a focus on monitoring [a person’s] wellbeing, stabilise it if we need to as clinicians, but generally using the existing support network they have. We promote their self-care advice, we encourage them to engage socially with the networks that they have, we encourage them to reduce or limit their alcohol or drug use, and then we say we’re going to follow you up. And this is very, very clear, because actually what we’re talking about is psychological first aid.”

The alternative: psychological first aid (PFA)

Psychological First Aid (PFA) is the modern approach to critical incidents and disasters. Its premise is that people are resilient and in most cases can recover naturally from trauma.

PFA is a “humane, supportive response to a fellow human being who is suffering and who may need support”, says the WHO. This involves helping people feel safe, connected to others, calm and hopeful, and ensuring access to physical, emotional and social support. It aims to reduce initial distress, meet current needs, promote flexible coping and encourage adjustment – and it can be delivered by managers and colleagues.

“Most people recover naturally from trauma, without the need for formal mental health intervention. For individuals who might benefit from trauma support, this is best provided in a style, on a timeframe, and by a practitioner who best suits the needs of that individual,” says Sonder’s Dr Phillips.

Five principles of PFA

Summary

Professor Bryant’s article is a timely reminder of the myth that all employees need psychological debriefing after a critical incident at work.

Given how important it is for employers to correctly channel their duty of care, HR and WHS leaders should immediately check:

(i) Their internal stakeholders are aware that psychological debriefing is against national and global best-practice guidelines; and

(ii) Their organisation does not subscribe to an outdated practice which might be putting both their employees and organisation at risk.

Download our myth-busting report

The myth that all employees need psychological briefing after a traumatic incident is included in our report, 5 myths of employee wellbeing, which we invite you to download here. (You can also watch Dr Jamie talk about these myths here.) This report will:

- Help you design employee wellbeing strategies that are evidence-based

- Share references and statistics you can use for your business case

- Dispel employee wellbeing myths that may be costing you time, money, and ESG results

Want to learn more?

For more information about how Sonder can help you rethink your employee and/or student support, we invite you to contact us.

About Sonder

Sonder is a technology company that helps organisations improve the wellbeing of their people so they perform at their best. Our mobile app provides immediate, 24/7 support from a team of safety, medical, and mental health professionals – plus onsite help for time-sensitive scenarios. Accredited by the Australian Council on Healthcare Standards (ACHS), our platform gives leaders the insights they need to act on tomorrow’s wellbeing challenges today.